From one system to many: Building an organisation-wide design system that accelerates, not obstructs

As common in most large organisations, we already had multiple design systems. Each had grown up around its own product line, with its own team, governance, and quirks.

On paper, this wasn’t a problem — each system worked fine for the product it served. But for the Accelerator, whose role was to launch new products and ventures quickly, this created a serious challenge.

If we adopted an existing system, we’d inherit its brand assumptions and technical constraints. Many of these systems had been built with different priorities in mind, which made them less adaptable for the Accelerator’s needs. Updates often took longer to flow through, and we needed a model that could move at the pace of new ventures. On the other hand, creating a new system for every project would waste time, resource, and energy duplicating foundations. Neither path was sustainable.

Team

J.P. Morgan Accelerator

Year

2024 - 2025

Role

Design System Lead

The Challenge

Designers and partners needed flexibility at scale, but existing systems were costly, under-resourced, and inflexible — leading teams to create their own.Too Many Systems

Each system was optimised for its own context but made it harder to work across products.No Shared Foundation

Brand and product teams wanted flexibility, but engineers needed consistent, reliable code.Resource Drain

New projects risked spinning up new design system teams — expensive, slow, and hard to sustain.

The Opportunity

Our Design System wasn’t created to be another design system. It was created because the organisation already had several systems — each tied to a single brand, with rigid rules and slow update cycles. This left designers without the flexibility they needed and pushed teams to spin up their own ad-hoc solutions, multiplying cost and inconsistency. The opportunity was to create a single, federated system: one that could flex across brands and products, scale without duplication, and give teams freedom within a unified framework. The system solves not just for consistency, but for collaboration across an entire organisation. This would allow us to:- Unify design and engineering through shared tokens and foundations.

- Flex across brands and products without breaking or duplicating.

- Scale sustainably by avoiding the need for a full system team per venture.

- Encourage collaboration across design and engineering teams.

My role

As design system lead, I was responsible for:Selling the idea internally

Framing the system as not “another system,” but the system that would save time, avoid silos, and accelerate new product launches.Designing the architecture

Creating a system-of-systems model with a layered token structure (core, semantic, thematic) that allowed brand flexibility without fragmentation.Defining governance

Establishing contribution and adoption processes so teams could both benefit from and improve the system.Building partnerships

Working closely with engineering to ensure design parity with code, and with brand teams to make sure visual expression wasn’t compromised.Leading the team

Managing a small, but effective design system team while coordinating with product and engineering stakeholders across the Accelerator.

The Approach

Grounding the system in the organisation’s needs and the pain points of existing systems was essential to its success.

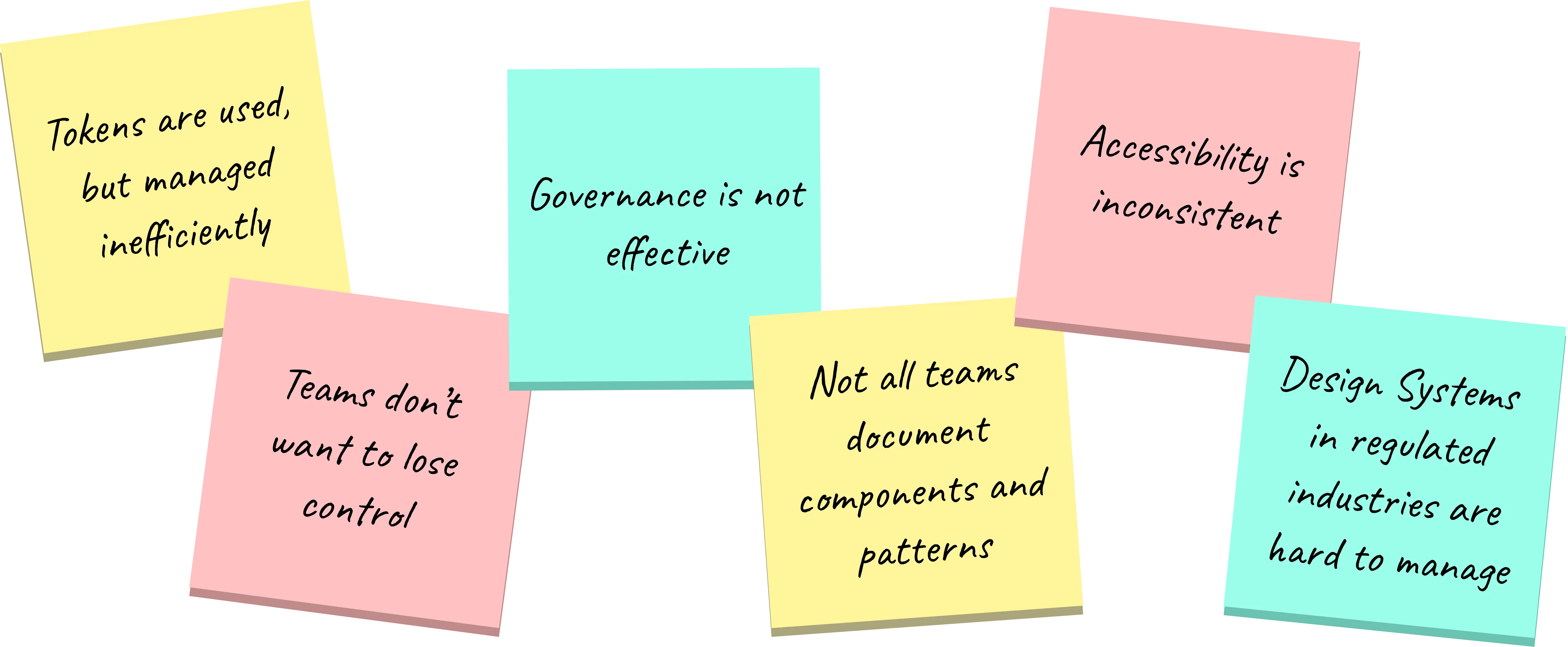

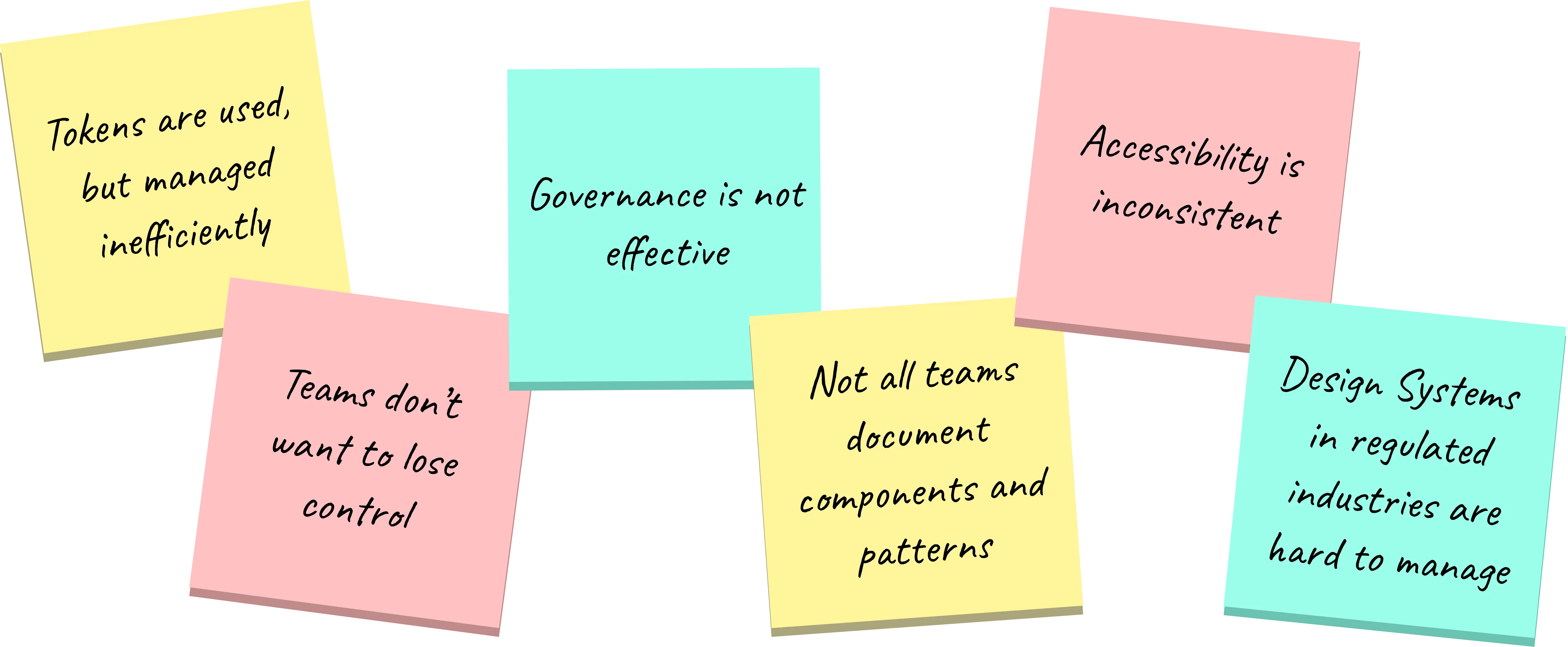

Before building anything, we focused on understanding the organisation’s needs and why existing design systems weren’t working. Designers felt constrained, business partners struggled with inconsistency, and teams often built their own systems to fill the gaps. Our system had to solve these issues from the ground up.

What we found

Understanding ecosystems inside and outside the firm

Listening to designers and partners, mapping out the pain points of existing systems, and identifying why duplication kept happening when design systems were needed.

Often, it was in response to an expectation of speed. But in reality, duplication only slows teams down.

Designing for scale and flexibility

We knew that the organisation needed an unlimited number of variables to contend with. Multiple platforms, mobile, desktop, native, potentially even wearables. So we needed to create an architecture that could support multiple products and brands without constraining creativity or individual choices teams would make.

Enabling streamlined governance

Setting up lightweight structures to ensure consistency, quality, and shared ownership.

Governance was present in most systems, but at varying levels. This meant the design systems were not as effective as they could have been.

Any ownership models would also have to be carefully considered to avoid teams feeling a loss of control.

Driving adoption through collaboration

Some design systems didn’t involve all partners in the business. So it was important that any new initiative involved partners working across design, engineering, and business teams so that the system could solve real problems rather than dictating from the top down.

I saw that this new initiative could only be successful by the collaboration with its partners. So a model where people felt a collective ownership and adoption model was important.

Framing for impact

Positioning the system as more than a “design system” — as an enabler of efficiency, speed, and unified design across the organisation.

Design systems are more than a component library. And from the systems we researched, many were only operating at that level. I had a vision for our system where this initiative could be more than a component library and truly enable efficiency at scale.

Drafting the architecture

For the system to be set up for success, the system architecture would need to work for each team who would utilise it

I adopted a system of systems architecture with a core foundation and connected product systems enables streamlined centralised governance while empowering teams with the flexibility they need. This approach allowed me to maintain consistent standards in the core system, while product teams can extend and customise components to meet their specific user needs. In terms of ownership, the core team maintains the foundational components and patterns, while product teams retain autonomy to innovate and iterate in their connected system(s). This architecture also provides better scalability for the core team, as we could focus on evolving the core system strategically rather than managing every component variation across each product/business. Ultimately leading to reduced maintenance overhead.

The Core System

At the heart of the system is the Core built to serve as a foundation across multiple products and brands. Instead of prescribing rigid solutions, the core provides the essential building blocks:

A unified set of tokens for colour, typography, spacing, and motion — designed for accessibility and flexibility.

Reusable UI elements, coded and designed in parallel, ensuring parity between design files and production.Often, it was in response to an expectation of speed. But in reality, duplication only slows teams down.

Common interaction models and guidelines that reduce duplication and promote consistency across journeys.

A semantic structure that allows the same core components to adapt seamlessly to different brands, markets, and contexts.

Connected & Sub-Systems

The connected system ensures that the design system adapts to the varied needs of the organisation. It links the core to specific contexts — brands, products, or business units — without forcing each to reinvent the wheel.

Semantic tokens allow colours, typography, and motion to be re-themed while retaining structural consistency.

Layered libraries that address the needs of particular journeys (e.g. payments, onboarding, or servicing) while remaining aligned to the core.

Contribution models where teams can extend the system responsibly, with updates flowing back into the core when relevant.

Sub-Systems Product sub-systems → Tailored component sets for individual products, built on the same foundations but with domain-specific rules. Brand sub-systems → Visual extensions that reflect unique brand expressions, ensuring parity across marketing and product. Experimental sub-systems → Sandboxes for testing new patterns or technologies, feeding proven solutions back into the system.

Sub-Systems Product sub-systems → Tailored component sets for individual products, built on the same foundations but with domain-specific rules. Brand sub-systems → Visual extensions that reflect unique brand expressions, ensuring parity across marketing and product. Experimental sub-systems → Sandboxes for testing new patterns or technologies, feeding proven solutions back into the system.

Extending the architecture

With the architecture established, the next step was designing the system’s spine — a robust token framework to hold everything together.

To keep everything tied together, we built a robust token framework — think of it as the spine that holds the system upright. Tokens are the building blocks behind the scenes, making sure colours, type, spacing, motion and more stay consistent no matter which team is using them. By planning this framework carefully, we gave designers and engineers the freedom to adapt and theme their work. It meant the system could flex across brands and products while still feeling like one connected system.

Building the token framework

We didn’t start from scratch. The first step was desk research: digging into how other design systems — both inside and outside the organisation — approached tokens. This gave us a sense of the best practices, the pitfalls, and how far we could push things.

Next came an audit of existing systems. Each brand and product team had its own way of handling tokens, often overlapping in places but clashing in others. By mapping them out, we could see what was genuinely useful, what was slowing people down, and where teams were creating workarounds.

We found that most teams wanted tokens to be clear and recognisable at a glance — especially for people who weren’t yet familiar with how tokens worked. This clarity also made it easier for Design and Engineering to cross-reference tokens during QA, keeping everyone on the same page.

Utilising Token Tiers

When it came to writing the tokens, it wasn’t just about coming up with names. It was about shaping a whole system of tokens that would make sense across design and engineering, and scale as the system grew.

Base tokens

We started with the base tokens — the raw values like hex codes for colours, pixel values for spacing, or timings for motion.

These would mostly form part of the individual brand theme and allow other levels of tokens to reference base values.

Semantic tokens

On top of that sat the semantic tokens — names that gave those values meaning. This layer let us adapt themes for different brands and products without breaking consistency.

Component tokens

We introduced component tokens — tokens that mapped directly to how a component looked or behaved. For example, a button could reference its background, text, or corner radius through component tokens, all drawing from the same underlying system.

This meant components could be fully white-labelled and customised by the teams using them.

Writing the tokens

A common challenge with tokens is inconsistency: if they aren’t named in a uniform way, their purpose becomes unclear and adoption suffers. For tokens to be effective, they must be instantly recognisable. Beyond establishing a tiered architecture, we defined a naming convention designed to scale with the system, ensuring clarity and consistency across teams.

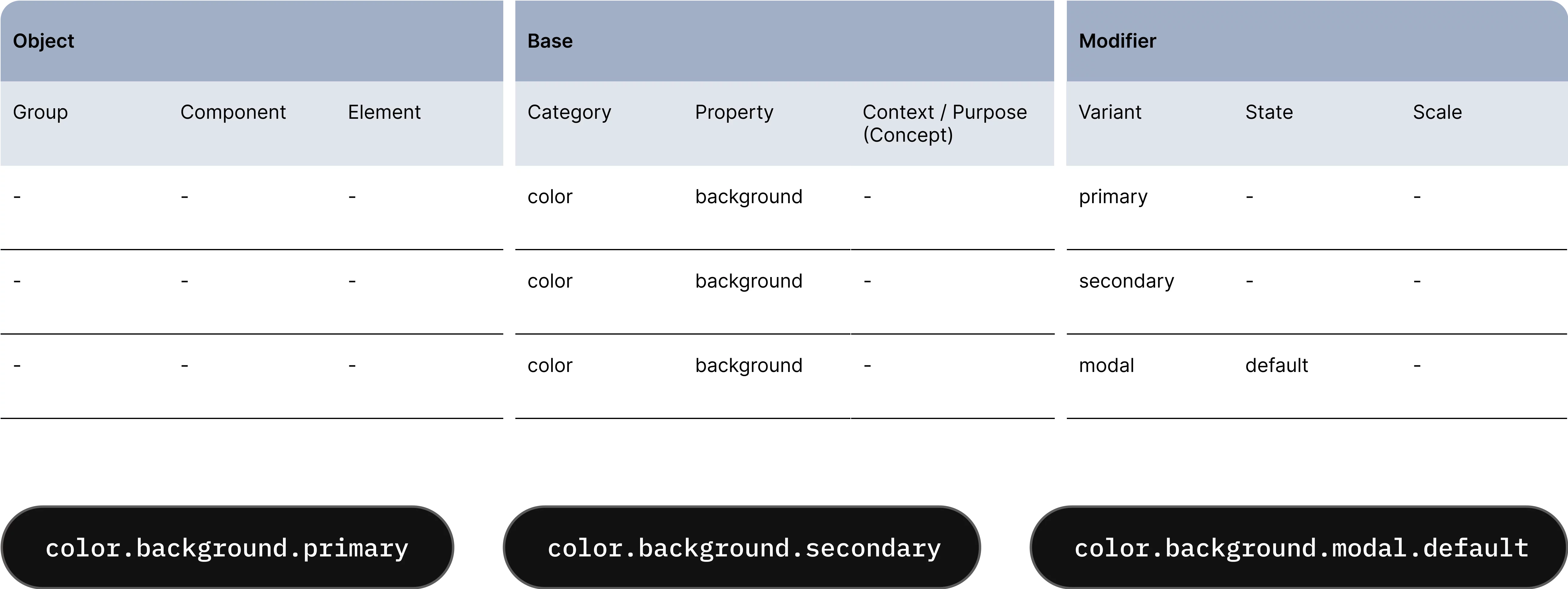

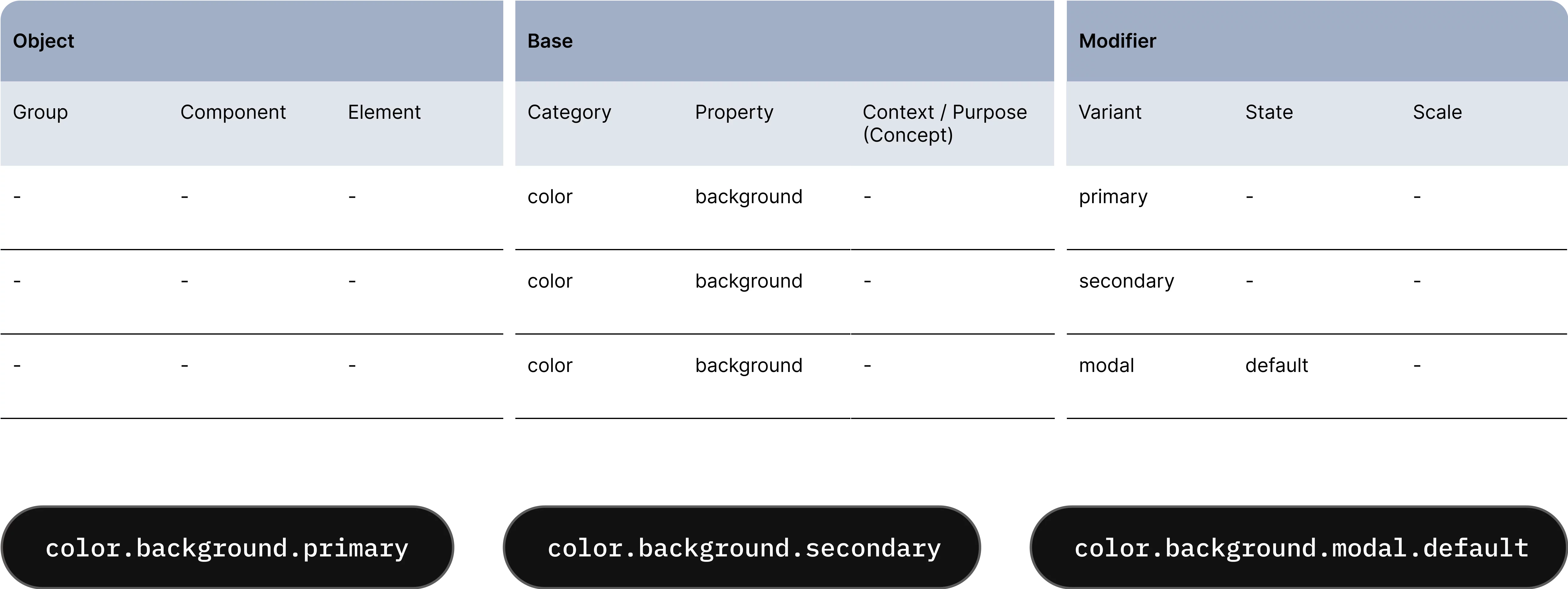

We introduced a structured naming convention built around four parts: Theme, Object, Base and Modifier.

This gave us a scalable system where tokens were easy to recognise, ready to use, and consistent across teams.

Token Constructor

I designed the Token Constructor to help the Design System team follow the naming convention. The table helps teams visualise where specific names sit as part of a whole token name. It also makes it easier to peer-review token names before they are submitted to development teams.

I designed the Token Constructor to help the Design System team follow the naming convention. The table helps teams visualise where specific names sit as part of a whole token name. It also makes it easier to peer-review token names before they are submitted to development teams.

After setting up the token architecture, the next step was to define the components and patterns that would make the system useful in practice

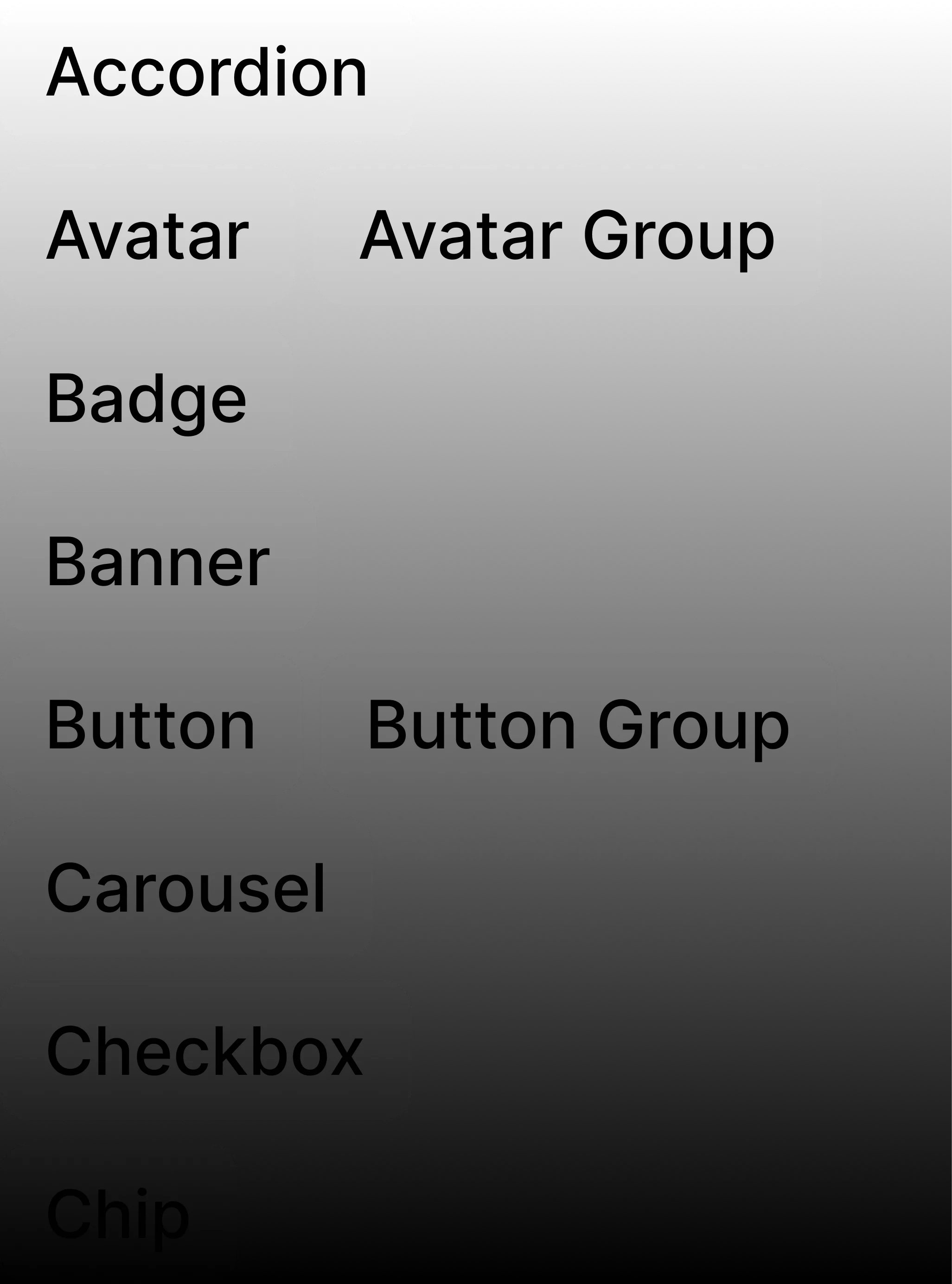

I started by revisiting atomic principles — keeping things modular, reusable, and composable. That meant beginning with the smallest pieces, like buttons and inputs, then combining them into larger structures such as forms, cards, navigation, and tables. From there, we extended into organisms and templates that solved real product needs at scale.

Because the system needed to flex across multiple products and domains, higher-order assets like templates and pages were less valuable as shared artefacts. Instead, they served more as guidance and behavioural best practice. Most teams created their own organisms, templates, and pages within their connected libraries, since these reflected the unique contexts of their products.

Reviewing major design systems inside and outside the organisation helped define which components should sit in the Core library.

Benchmarking against major design systems both within our organisation and across the industry, gave a baseline sense of the usual foundations, but the more important signal came from looking at our own teams. Wherever we saw multiple teams independently designing and maintaining the same component, that was a strong case for including it in Core. The goal isn’t to centralise everything, but to identify the shared building blocks that would deliver the biggest efficiency gains and consistency benefits at scale.

48

Components16

Patterns

The Core library wasn’t designed to cover every product need, but to provide the major reusable building blocks that most teams would otherwise recreate. By consolidating these into the system, we saved time, ensured consistency, and gave teams space to focus on the unique aspects of their products.

Accessibility from the start

Accessibility wasn’t treated as an afterthought in the system. From the beginning, I applied a “shift-left” approach — meaning accessibility was built into the system at the earliest stages rather than retrofitted at the end of delivery. Any team adopting Lumen automatically started from an accessible baseline. Instead of teams having to “make their work accessible” late in the process, the system gave them a foundation that was accessible by default. Built-in compliance

WCAG 2.2:

All colour, typography, and interaction decisions were tested against the latest Web Content Accessibility Guidelines to ensure minimum AA compliance by default.

EAA (European Accessibility Act):

Components were designed to anticipate requirements for products distributed across Europe, ensuring the system could scale globally without creating compliance gaps.

ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act):

Accessibility standards relevant to US-based products were considered upfront, ensuring parity across markets.

Token-driven accessibility

Because components were built on tokens, accessibility could be enforced consistently:

- Colour tokens locked in minimum contrast ratios.

- Spacing and typography tokens ensured legibility and touch targets.

- Motion tokens supported reduced-motion preferences.

Governance & Contribution

A design system is only as strong as its governance. From the start, I knew the system needed to strike a balance: consistent enough to be trusted, flexible enough to be adopted.

Clear ownership

We defined which elements lived in Core (tokens, foundations, core components) versus which belonged in connected libraries (product-specific organisms, templates, and pages). This separation meant Core stayed stable, while teams still had room to innovate within their own domains.

We also made it clear who made changes to core code, design and documentation and who was expected to maintain each of these.

Contribution model

I set up a transparent contribution process so teams could feed improvements back into the design system without creating chaos.

- Proposals were submitted with rationale and examples.

- Changes were reviewed by a cross-functional group (design + engineering) for quality, accessibility, and impact.

- Once approved, updates flowed back into Figma and code at the same time, keeping parity intact.

Versioning and breaking changes

Managing change was critical to keeping trust in Lumen.

- We introduced semantic versioning so teams could clearly see whether a release contained fixes, new features, or potential breaking changes.

- Breaking changes were rare and only introduced when essential, such as for accessibility compliance.

- Where breaking changes occurred, they were supported with deprecation periods, migration guides, and clear communication, ensuring teams had time and confidence to update.

Adoption pathways

Governance wasn’t only about control — it was also about making adoption easy.

- New teams received onboarding guidance and starter kits.

- Documentation and usage guidelines were written to feel human and practical, not just technical.

- Regular system reviews gave teams confidence that their needs were being heard.

Reflection & Future Evolution

Leading the design system reinforced an important lesson for me: design systems are never just about components or tokens — they are about people, trust, and scale. The technical architecture mattered, but what made the difference was creating a system that teams actually wanted to use. Earning that trust meant listening, making adoption easy, and being deliberate about when to centralise versus when to let teams build their own solutions. I also learned that a design system’s success is not measured by how much it controls, but by how much friction it removes. The moments I’m proudest of were when teams could launch faster, solve problems more confidently, and know accessibility was already covered because of the system we built. Looking forward, I see huge potential for AI-driven automation in design systems. For our design system, that could mean:- Automated auditing of Figma files for accessibility or token compliance.

- Intelligent suggestions when designers stray from Core patterns.

- Automatic mapping of new design variants back to system tokens.

- Real-time parity checks between design and code.

Danny Skinner